“Coloured people don't like Little Black Sambo. Burn it. White people don't feel good about Uncle Tom's Cabin. Burn it. Someone's written a book on tobacco and cancer of the lungs? The cigarette people are weeping? Burn the book. Serenity, Montag. Peace, Montag. Take your fight outside. Better yet, into the incinerator.” Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451

Jack Dempsey Brock (1927–2020) was “sacrificially committed and supernaturally called to serve and reach people with the gospel of Jesus Christ,” said an obituary in Alamogordo Daily News. After spending much of his youth as a travelling evangelist, Brock and his wife Sharon had settled in Alamogordo, a city with some 69,000 inhabitants located at the western base of the Sacramento Mountains in New Mexico where he founded Christ Community Church in 1973 and continued as its pastor until his death on April 3, 2020. According to his obituary, his greatest accomplishment was his 70+ years of teaching the Word of God. Yet, it was not dedication to the gospel that earned Jack Brock a place in international headlines.

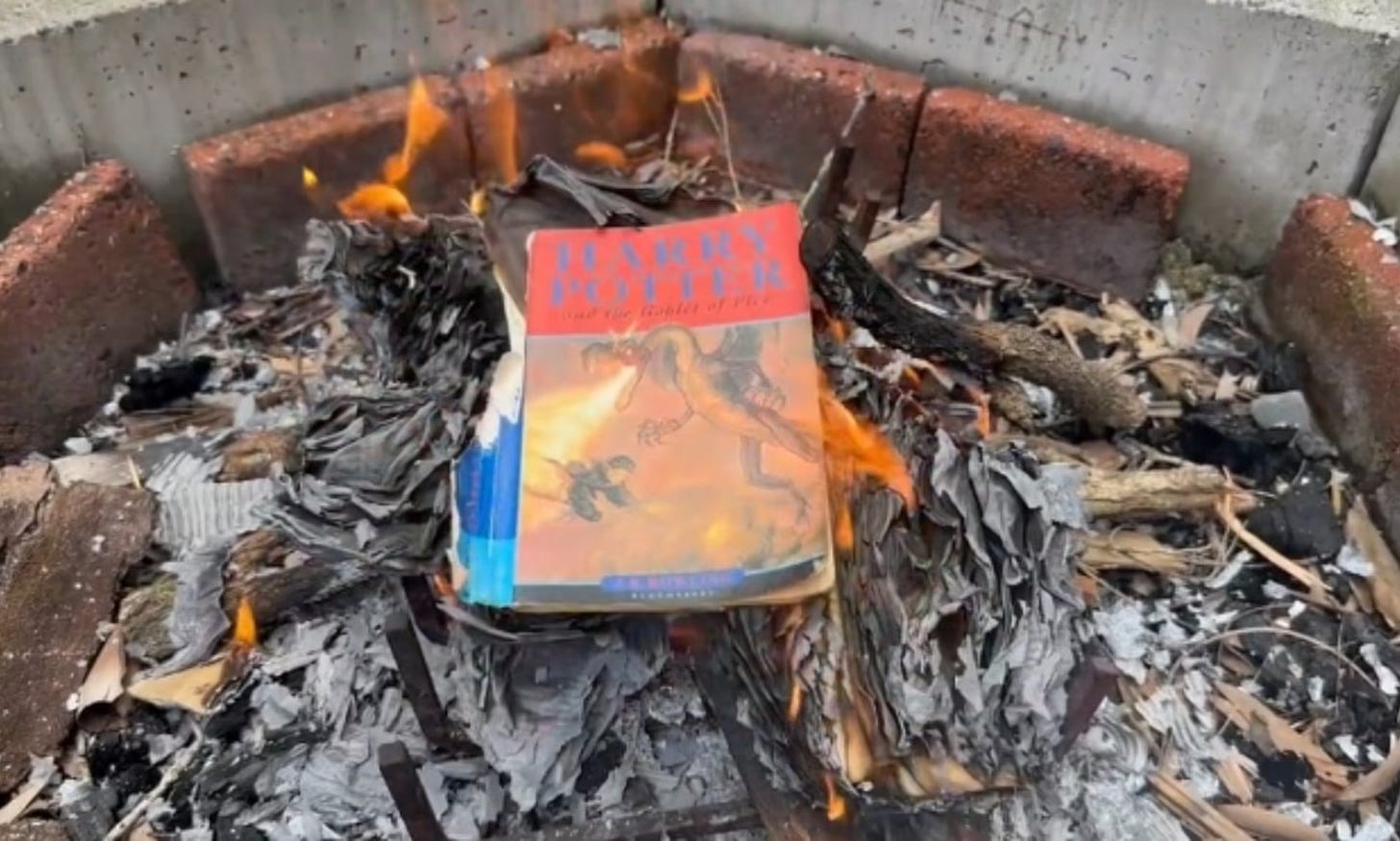

On December 26, 2001, Pastor Brock announced that he would hold a bonfire to burn Harry Potter books because the famous series of fantasy novels by British author J. K. Rowling about a teenage wizard was “an abomination to God and to me.” However, he also admitted he hadn’t read any of them. “These books teach children how they can get into witchcraft and become a witch, wizard or warlock . . . Behind that innocent face is the power of satanic darkness,” he told his congregation in a sermon delivered on the night of Sunday December 30. The sermon was followed by a ceremony of book burning, where Brock threw some 30 Harry Potter books into the fire while members sang “Amazing Grace” with their faces lit by the glow of the flames.

Jack Brock was not the only evangelist who felt threatened by Rowling’s hugely popular young wizard Harry Potter and his friends, Hermione Granger and Ron Weasley. Another was Reverend Doug Taylor of Jesus Party Church, a Pentecostal congregation in Lewiston, Maine, whose attempt to burn the Potter books was thwarted by the city’s refusal to grant him a burning permit. Instead, Taylor went ahead by staging a “book-cutting” event: “Everybody’s going to have scissors, and we’re going to cut those four [Harry Potter] books up right into the trash.” “It’s no secret that I enjoy what I’m doing right now,” Taylor said while he shredded Rowling’s book, as one of his flock shouted “Hallelujah.”

Since the release of the first movie adaptation of the series, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, in 2001, there have been at least six public burnings of Harry Potter books in the US alone, for allegedly promoting witchcraft and Satanism. The numbers swelled when Donald Trump supporters jumped on the bandwagon, after Rowling’s public condemnation of Trump’s immigration ban on citizens from Muslim-majority countries in 2017. “Just burned all my Harry Potter books after being a fan for 17 years . . . You embarrassed me, disgusted me, and I will never read your work again,” an angry user tweeted at J. K. Rowling who replied: “Guess it’s true what they say: you can lead a girl to books about the rise and fall of an autocrat, but you still can’t make her think.”

As a seasoned writer, Rowling was probably aware that despite her growing notoriety among far right pyrophiles, she was far from being the first or the most hounded author whose books were being ceremonially incinerated to protect gullible readers from the corrupting influence of the written word.

Book burning, or the deliberate and ritual destruction by fire of books, is a centuries-old tradition whose origins go back to Chinese Qin Dynasty (213–210 BC). Since then, there have been countless instances of public book burnings, by both religious orders and secular authorities, from the expurgations of Jewish and Christian scriptures by Ancient Greeks and Romans to the burning of Voltaire and Rousseau’s books in Paris and Geneva. Book burning fell from grace with the Enlightenment, only to be rekindled in the runup to and during the First World War, first by “patriotic fires,” which involved the burning of pro-German and pacifist writings, then the burning of the library at Louvain University by German occupying forces in August 1914. International outrage caused by this act of wanton violence led the German government to produce a report absolving its military command of any deliberate intent, but the report was dismissed elsewhere and, with hindsight, could even be read as an ominous portent for things to come.

Almost two decades later, on the night of May 10, 1933, some 40,000 students, backed up by uniformed brown shirts of the paramilitary SA, gathered in the Opernplatz (now the Bebelplatz) in the Mitte district of Berlin to celebrate the “Action against the Un-German Spirit,” a nationwide campaign to purify the German language and literature launched by the Nazi German Student’s Association’s Main Office for Press and Propaganda. Amidst cheers, joyful singing, and fire oaths (the so-called Feuersprüche), a group of students marched up to the bonfire carrying the bust of the Jewish founder of the Institute of Sexual Sciences, Magnus Hirschfeld, and threw it on top of thousands of volumes from the institute’s library, along with other books by Jewish and “un-German” writers. The fire was surrounded by rows of young people in Nazi uniforms giving the Heil Hitler salute, while listening to the speech delivered by Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels who orchestrated the whole event:

No to decadence and moral corruption! Yes to decency and morality in family and state! . . . The future German man will not just be a man of books, but a man of character. It is to this end that we want to educate you . . . You do well to commit to the flames the evil spirit of the past. This is a strong, great and symbolic deed.

That night, students in 34 university towns across Germany burned over 25,000 books by more than 75 German and foreign authors. Among the many authors whose books were burned was the famous nineteenth-century German poet and playwright Heinrich Heine who had written the horribly prescient words almost a century earlier, in his 1821 play Almansor: “Where they burn books, they will, in the end, also burn people.”

The burnings of May 10 were just a drop in the ocean, as Bodley’s librarian Richard Ovenden notes in his magisterial Burning the Books: A History of the Deliberate Destruction of Knowledge: “over 100 million books were destroyed during the Holocaust, in the twelve years from the period of Nazi dominance in Germany in 1933 up to the end of the Second World War.” This was what prompted American author Ray Bradbury to write one of the greatest contributions to dystopian fiction in the twentieth century, Fahrenheit 451. In an interview he gave in 2005, Bradbury explained how he came up with the idea of a bleak future where fire departments burn books:

Well, Hitler, of course. When I was 15, he burned the books in the streets of Berlin. Then along the way I learned about the libraries in Alexandria burning 5000 years ago. . . . That grieved my soul. Since I’m self-educated, that means my educators – the libraries – are in danger. And if it could happen in Alexandria, if it could happen in Berlin, maybe it could happen somewhere up ahead, and my heroes would be killed.

Unfortunately, heroes continued to be killed, for all sorts of reasons and by all sorts of regimes – as Bradbury himself was painfully aware. When asked about the burning of Harry Potter books in 2006, the 86-year-old author said he thought Reverend Doug Taylor and his ilk were deluded. “He [Reverend Taylor] doesn’t know what witchcraft is,” he continued. “It’s about wits. There’s nothing wrong with the Potter books, because they’re not promoting witchcraft. They’re promoting being wise.”

This is the first part of an excerpt from my recently published book, Cancelled: The Left Way Back From Woke (Polity, 2023). The book is available on all major online platforms and bookstores. The Spanish edition of the book, Cancelados: Dejar atrás lo woke por una izquierda más progresista will be published on October 18 (Paidós/Planeta, 2023).