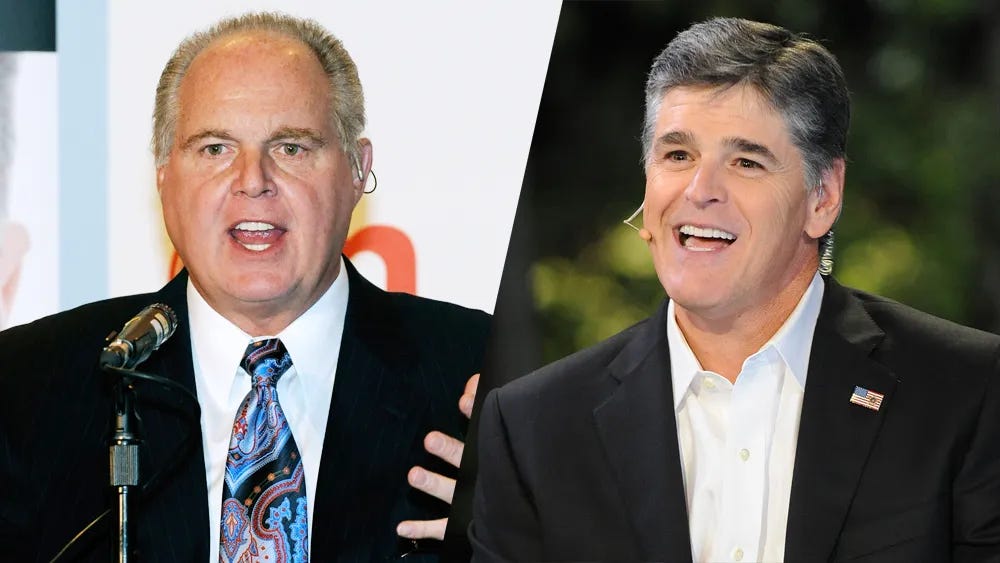

When academics Jeffrey M. Berry and Sarah Sobieraj wrote their book The Outrage Industry: Political Opinion Media and the New Incivility in 2014, their aim was to explore the new genre of political opinion media they called “outrage,” which is defined by the rhetoric it uses, “its hallmark venom, vilification of opponents, and hyperbolic reinterpretations of current events.” Controversial and provocative content has always been part of the US media landscape, they conceded, but the sheer volume and popularity of outrage-based commentary, particularly on the Right, made it a new ball game. In the early 2010s, at the time of the publication of the book, influential right-wing media personalities like Rush Limbaugh or Sean Hannity attracted 15 and 14 million weekly listeners to their respective radio shows. Berry and Sobieraj’s overall estimate for talk radio, using data for the top 12 hosts, was roughly 35 million listeners daily.

Even though the book was focused on the development of the genre in the right-wing media landscape, the authors did not shy away from pointing to the commonalities between the Right and the Left:

the way conservative and progressive commentators use outrage unites them . . . Consider practices such as using ideologically extremizing language (e.g., describing someone as “far-right wing” or “far-left wing”), “proving” an opponent is a hypocrite (often with decontextualized quotes offered as evidence), presenting their version of current affairs as the “real story” and other accounts as biased. Taken together, we find remarkable mirroring between conservatives and progressives. There are scripts that could easily be rewritten for the other side by simply replacing the nouns.

I cannot help but wonder whether Berry and Sobieraj would be able to write this in 2022 without attracting the ire of online outrage mobs from both sides of the political divide. For the Right, what we are witnessing today is a “free speech” crisis generated by woke takeover of institutions of higher education, a process which can only be reversed by “external government intervention.” For the woke Left, this is simply right-wing propaganda. Regurgitating the argument from accountability and agency, Jason Stanley and Kate Manne claim that free speech is being co-opted by privileged groups and “distorted to serve their interests, and used to silence those who are oppressed and marginalized.” Nesrine Malik doubles down in The Guardian and argues that “The purpose [of the myth of the free speech crisis] is to secure the licence to speak with impunity; not freedom of expression, but rather freedom from the consequences of that expression.”

But the outrage industry is not the outcome of a free speech crisis, for the issue is not whether speech is restricted or not. It is about what counts as free speech and who makes that decision.

Conflict over the definition of free speech, or to recall the expression used in official definitions of cancel culture, the boundaries of what is culturally acceptable and what is unacceptable, is the oil that greases the wheels of the outrage machine. And it is here that the reactionaries and the woke Left team up. The Right is completely blind to reactionary cancel campaigns or, more generally, the all-out assault on fundamental rights and freedoms by conservative (at times openly and proudly illiberal) legislatures and executives all around the world. One need only mention the recent Supreme Court decision to overturn the constitutional right to abortion which was established by the landmark 1973 ruling in Roe v Wade, or the slew of anti-Critical Race Theory bills and educational gag orders that target speech about LGBTQ+ groups (and this is only the US). The woke Left, on the other hand, is more concerned with policing speech and identifying microaggressions among fellow progressives than building a common front against the Right’s transgressions. Much like the Right, it is oblivious to egregious breaches of fundamental freedoms when they are committed by what they perceive as disadvantaged groups, claiming the authority to determine who the victims and the perpetrators are. This move allows them to create a false moral binary between freedom of speech on the one hand, and the sanctity of life on the other – a tripwire blocking the road to progress.

But why do new activists retreat into performative outrage instead of fighting for real change?

Is it because they lack the courage or the organizational skills to take on actual centers of power, as Chris Hedges claims? Or is this an inevitable outcome of the commodification of identity which, with the encouragement of legacy media and big corporations, also leads to the domestication of progressive politics? Outrage provokes emotional responses from the audience, Berry and Sobieraj inform us, through the use of “overgeneralizations, sensationalism, misleading or patently inaccurate information, ad hominem attacks, and belittling ridicule of opponents.” More importantly, it “sidesteps the messy nuances of complex political issues in favor of melodrama, misrepresentative exaggeration, mockery, and hyperbolic forecasts of impending doom.” It creates a safe space for those who think alike, not only reducing potential risks for the participants, but also producing a sense of community and belonging, by isolating them in echo chambers.

At the end of the day, however, outrage kills politics. Or, in Hedges’ snappy formulation, “it turns anti-politics into politics.”

What the Left needs is a new vision that would break the outrage cycle, a socially and economically progressive agenda that would include all those who are negatively affected by rampant neoliberalism.