“Welcome home”, said the wise P. That was the shortest, yet probably the most meaningful, way of greeting someone who hasn’t slept in the same bed two nights in a row for several months. “I guess I needed to hear this”, I said in response. They were there to pick me up and drive me away, to a little town on Costa Brava. C, or Mamá Uno as I would soon start to call her, firmly clasped my hand, interlacing her fingers with mine. “That’s exactly how He would do it”, I thought to myself, when he was strapped to a hospital bed, often in pain, or when we were climbing down the steep stairs of our cozy nest at Stålbrogatan where we spent much of our earthly lives. Much like Him, C was persistent, not letting go of my hands while we drove silently in the thick darkness, pierced only by the frail light of the eclipsed moon.

Without any particular reason, at least on a conscious level, I thought of one of Leonard Cohen’s early songs “The Partisan”, trying to get my mind off the “hungry caterpillar” which was eating away my soul since that dreadful day, July 5, 2018:

When they poured across the border

I was cautioned to surrender

This I could not do

I took my gun and vanished.I have changed my name so often

I’ve lost my wife and children

But I have many friends

And some of them are with meAn old woman gave us shelter

Kept us hidden in the garret

Then the soldiers came

She died without a whisperThere were three of us this morning

I’m the only one this evening

But I must go on

The frontiers are my prisonLes Allemands étaient chez moi

Ils me dirent, “résigne toi”

Mais je n’ai pas peur

J’ai repris mon âmeJ’ai changé cent fois de nom

J’ai perdu femme et enfants

Mais j’ai tant d’amis

J’ai la France entièreUn vieil homme dans un grenier

Pour la nuit nous a caché

Les Allemands l’ont pris

Il est mort sans surpriseOh, the wind, the wind is blowing

Through the graves the wind is blowing

Freedom soon will come

Then we’ll come from the shadows

True, the conditions I found myself in weren’t hardly comparable to that of a French resistance fighter during the Second World War. I had also lost a child, but I had many friends who could give me shelter. Frontiers weren’t my prison. On the contrary, the world out there was less foreign than the place I used to call home for almost ten years years.

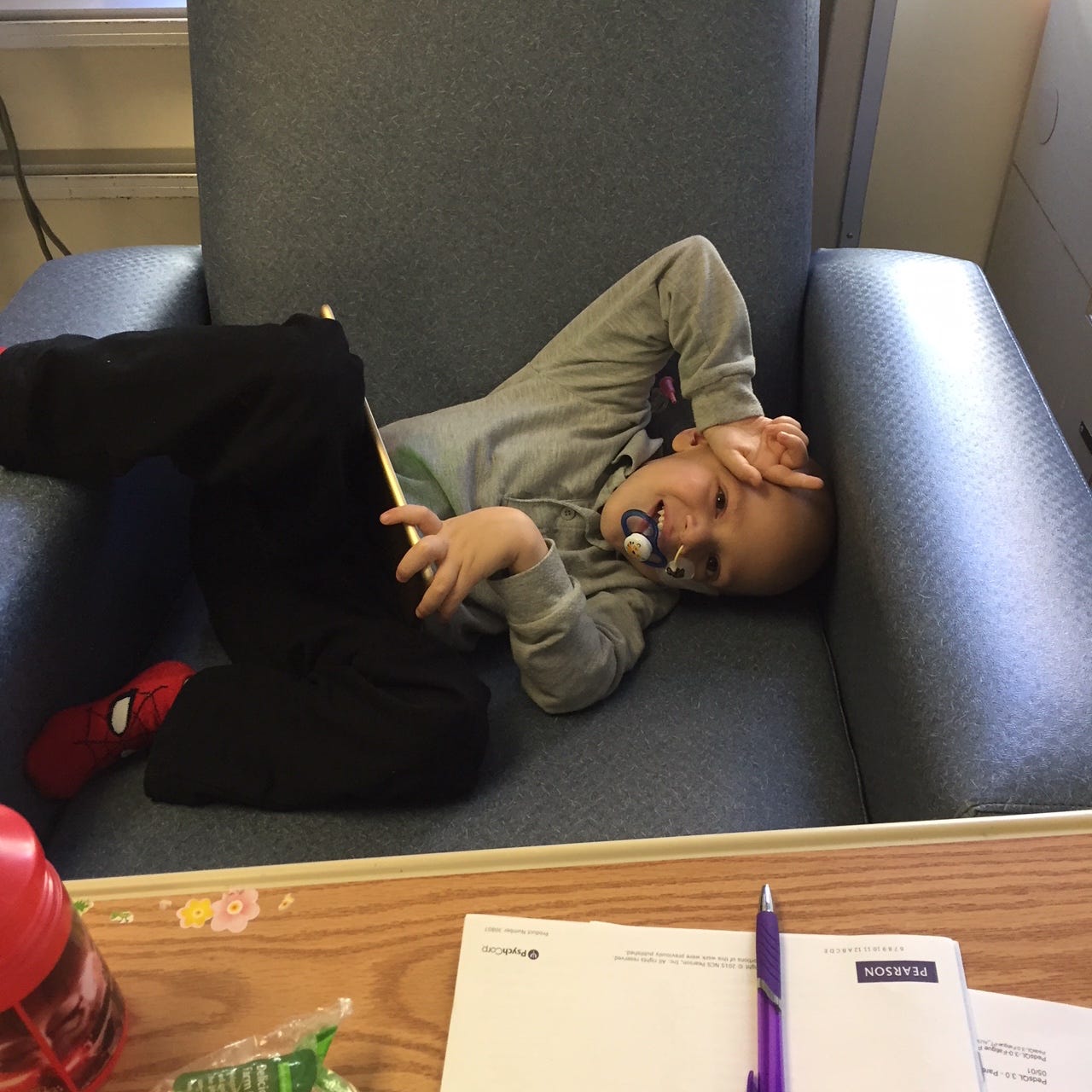

But the garret I was hiding in, the love that was poured on me since I began this new journey couldn’t fill the void I had within me. The bells of the little town church that rang at every quarter past the hour, the sand that was burning my feet, even Sixto, our charming dog , everything reminded me of Him. The sound of the bells were a replica of the ones he’d listen to every night before he went to bed; I had to carry him back on my lap for he couldn’t walk on the sand that burned his little feet. And Sixto. The late Sixto, his playmate, his joy, during the brief time he spent in what had now become my new home. There were the two of us then, I was the only one later. But I knew I also had to go on. For Him, for my friends, and my loved one. Was this also a form of “resistance”? A more mundane, and certainly, more trivial resistance? I felt it was.

And to continue to resist on a daily basis is an enormous challenge. Some nights, I only see morbid things the moment I close my eyes, often death itself. Those nights – most nights – I am scared to fall asleep. Other nights, I see nothing. The void inside morphs into a thick black curtain, covering over the cherished moments I shared with Him. I try to remember his face, but I can’t. I could look at his pictures, but I can’t do that either, without feeling suffocated that is. I know that I had a past, but I no longer know who I am. Or better, I no longer no who I’ve become. And I don’t always know what’s the purpose of life, why I keep fighting. After all, at least that’s what I tend to believe, to resist cannot be the sole purpose of life. Could it?

Perhaps it’s still too early to resist, to reinvent a new meaning for life. Perhaps I have to fathom, digest, internalize, and feel that I am still alive. I read and reread the text message that was sent by J, Mamá Dos: “Take your time. Don’t feel pressured about anything. Get in the sea, though. She will remind you about yourself! Float about and feel how good the water is.”

I obey. I get in the sea. I fill my lungs with her unique briny smell. I let her take me into her arms. While floating about, I look at the beach, the white houses and the little church that rose below the green hills.

“He would have loved these church bells”, I say to myself. “And He would have hated the bells of the Lutheran church we bid farewell to Him”. Was it possible to live - to resist - constantly thinking about what he would’ve loved or hated? Could this be the freedom that the Cohen’s Partisan talked about?

It is indeed too early to answer these questions, or to enjoy freedom – a freedom that was thrust upon me, and not on my own volition.

I cannot come from the shadows yet, for the shadows are my prison.

(This post was originally written on 4 August 2018. This is a revised and refined version.)